6 reasons to be wary of AI in planning

AI has great potential, but like a foghorn sounding a warning about approaching rocks, there’s an increasing number of voices expressing concerns about how AI may be used in planning. Here's six cautionary notes from the RTPI, the High Court and the Royal Society, amongst many others:

Caution #1. RTPI Practice Advice Note on AI

The RTPI Practice Advice Note on planning and AI published on 6th March 2025 cautions,

“Large Language Models are a specific type of Generative AI trained on the enormous amount of text available across the internet. LLMs can appear to understand context and generate responses that are coherent and often contextually appropriate. However, it is important to note that these models don't ‘understand’ context in the way humans do. This is because they operate by predicting the next word or phrase that is most likely to follow a given sequence of words, based on patterns learned from the ‘training data’. This process is purely statistical and doesn't involve any comprehension of meaning, intent, or the nuances of human thought.”

In other words, AI produces plausible text. It’s not in the same league as planning Inspectors’ carefully nuanced observations and weighed judgements. The trouble is, it’s too easy to forget this qualifier when reading AI produced material.

Caution #2. Royal Society scientific paper

A noteable scientific paper published on 30th April 2025 by the Royal Society tested 10 prominent AI Large Language Models (LLMs) including ChatGPT and DeepSeek by comparing 4,900 LLM-generated summaries with their original scientific texts. The scientific results were:

“LLM summaries were nearly five times more likely to contain broad generalizations. Notably, newer models tended to perform worse in generalization accuracy than earlier ones. Our results indicate a strong bias in many widely used LLMs towards overgeneralizing scientific conclusions, posing a significant risk of large-scale misinterpretations of research findings.” (source: 'Generalization bias in large language model summarization of scientific research' Uwe Peters and Benjamin Chin-Yee 2025

Experts are puzzled because the most recent LLMs are worse than earlier versions. No-one is yet able to explain the growing tendency for “AI-slop” to be of decreasing quality.

Does this matter? It does if legal and other decisions are being based on it. The law courts are becoming concerned and have started to address the issue.

Caution #3. High Court Judgment

A significant High Court Judgment published on 6th June 2025 found,

“Freely available generative artificial intelligence tools, trained on a large language model such as ChatGPT are not capable of conducting reliable legal research. Such tools can produce apparently coherent and plausible responses to prompts, but those coherent and plausible responses may turn out to be entirely incorrect. The responses may make confident assertions that are simply untrue.”

The Judgment referred to the Bar Council’s guidance which states,

"The ability of LLMs [large language models] to generate convincing but false content raises ethical concerns. Do not therefore take such systems' outputs on trust and certainly not at face value… the data used to 'train' generative LLMs may not be up to date; and can sometimes produce responses that are ambiguous, inaccurate or contaminated with inherent biases. Inherent bias may be invisible as it arises not only in the processing or training, but prior to that in the assembling of the training materials. LLMs may also generate responses which are out of context.”

In other words, never take LLM results at face value. You must always check the source.

Caution #4. Environmental impact on water and CO2 emissions

AI saves time, right? Yes, but for an environmentally-conscious profession like planning, there is a downside. AI requires massive energy consumption compared to traditional software, and in turn vast amounts of water are needed to keep AI data centres cool enough to operate. Newspapers are increasingly running articles on the clash between the Government’s push for AI and its drive for net zero. Internationally, the UN Environment Programme notes,

“Globally, AI-related infrastructure may soon consume six times more water than Denmark …. A request made through ChatGPT, an AI-based virtual assistant, consumes 10 times the electricity of a Google Search, reported the International Energy Agency.…. the agency estimates that in the tech hub of Ireland, the rise of AI could see data centres account for nearly 35 per cent of the country’s energy use by 2026.”

It’s difficult to square sustainability concerns with reliance on AI. One solution is to locate AI data centres in places like Iceland where it can use geothermal energy, but in turn this creates geopolitical security problems with undersea data cables being vulnerable to attack. Planning has many contradictions, but this sustainability conundrum takes us to a new level.

Caution #5. Aristotle

Roll in old-time wisdom. It turns out even Aristotle has something to say about AI, despite having died over 2,300 years ago.

A very interesting and thoughtful blog by Dr Daniel Slade, Head of Practice and Research at the RTPI, argues Aristotle brings useful insights into the planning profession’s relationship with AI. Daniel Slade writes,

“Aristotle argued that there were three types of wisdom: episteme, techne and phronesis. First, episteme (includes) scientific knowledge about why the world works as it does….. For planners, this may include economics, demographics, or ecology. Techne ….echoes in the English words ‘technology’ and ‘technique’…. For planners, this could be knowing how to use GIS for plan making or knowing the key stages of submitting a planning application. Aristotle’s third type of wisdom is phronesis (which) concerns practical, context-dependant, value-driven, wisdom.”

Daniel Slade sees phronesis as planning’s defining characteristic and notes,

“Planning is deeply political, and even relatively technical tasks like the submission of a planning permission require empathy and emotional sense. Public engagement very obviously requires this sense of the human experience and the values that communities hold. Indeed, the legitimacy of planning as a whole is grounded in the idea of decision making in pursuit of a shifting and subjective public interest, and the RTPI’s Royal Charter refers to the ‘art’, not just the science, of planning.

Phronesis is a useful concept because it reminds us that values, emotions, and the public interest are central to how planners make decisions – even when the tools being used are scientific or technical.

What this reveals about the profession’s relation to AI is that, as powerful a tool as it may be, it cannot (and should not) replace the expert judgement and discretion of professional planners, acting transparently.”

Caution #6. Personal experience of searching for appeals

I’ve found AI summaries do not replicate the carefully-worded nuances of an Inspector’s reasoning. They inevitably use commonly-used phrases and generalisations, which can obscure an Inspector’s fine distinctions and careful judgements. For example, between a matter which the Inspector thinks lends “support to the proposal” and another matter to which they attach “significant weight”.

I have also come across numerous examples of AI mis-categorising appeals on a competitor’s website, for example when the AI thinks the appeal is ‘agricultural development’ when in fact the development is a major housing scheme on agricultural land, or when the AI thinks an appeal is ‘permitted development’ when in fact the P.D. is the fall-back position not the development under consideration.

In my experience, AI-driven summaries should be treated with a healthy degree of scepticism and you should always refer to the original appeal, and never rely solely on the AI-produced summary.

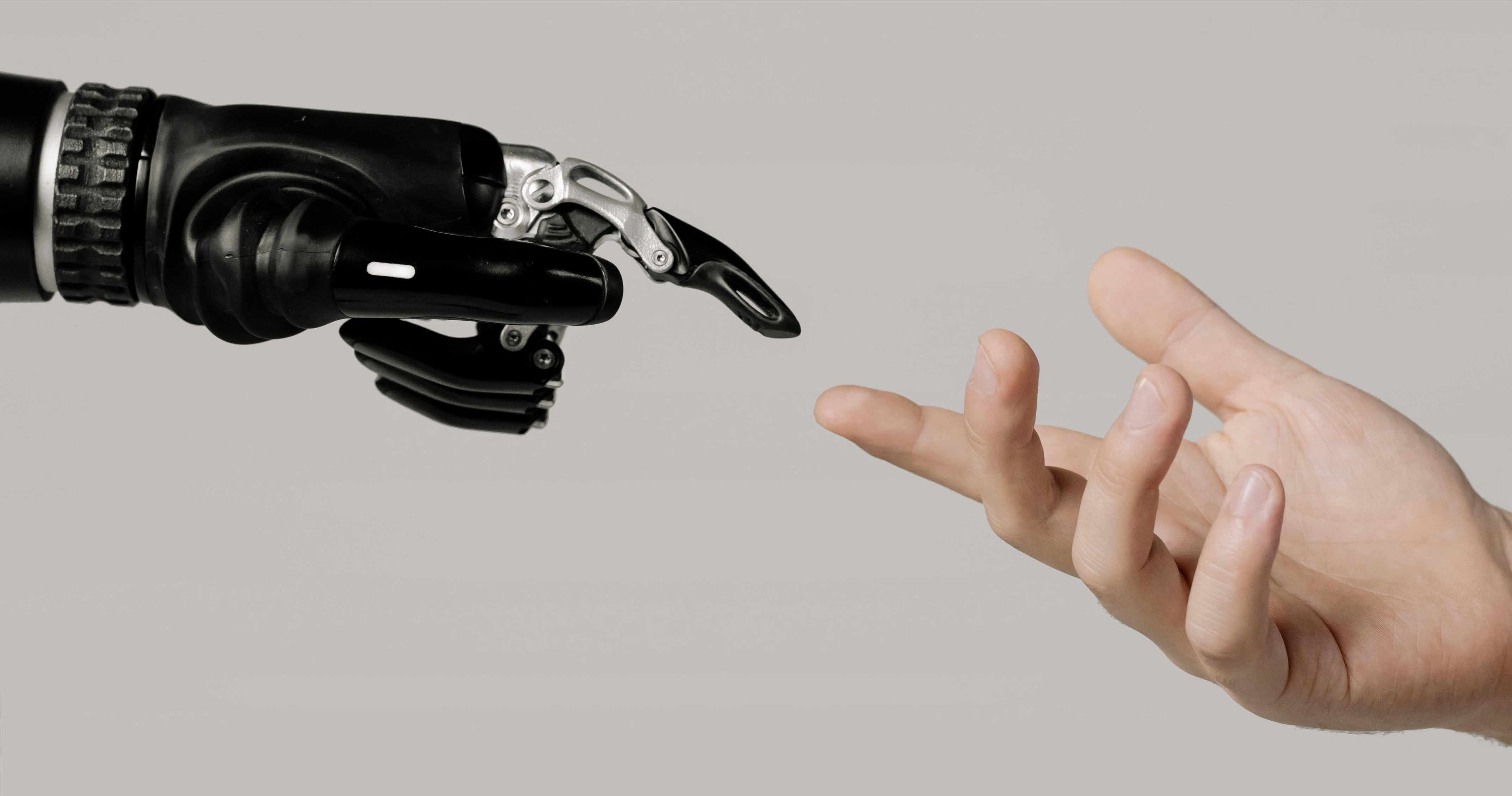

Is the future of planning Artificial Intelligence or Human Intelligence?

Where do the six reasons to be wary given above leave us? The clue is in the name: AI is artificial whereas decision makers on planning applications and appeals are human (unless Councils and PINS have a secret assembly line of robots waiting to be revealed…..?) As long as decision makers are human, AI is severely hindered by the fact it doesn’t think like us. AI can’t understand the political, emotional and moral judgements undertaken by decision-makers in the planning system. So its use in the planning system needs to reflect its limitations.